One Reality Isn’t Enough: A Call to Scale with Nuance

How Equity, Expertise, and Local Wisdom Shape Real Literacy Success

This post is free to read, so please ‘like’ it via the heart below and share the link widely. The best way to support my work is with a monthly, annual or licensing subscription.

Scaling Literacy with Nuance: What One Post Revealed About Excellence

Sometimes, it’s the smallest moments—a comment, a thread, a spark of curiosity—that pull us into our deepest thinking.

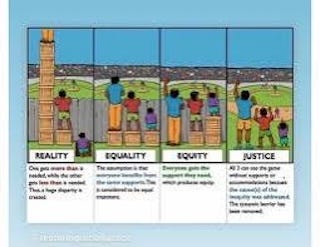

Literacy isn’t scaled in a vacuum. Like the familiar image of equity vs. equality, this article is about seeing and responding to the very real differences in district context, teacher capacity, and student need.

This idea came into sharper focus for me on a quiet Saturday morning when I posted a provocative literacy article on Facebook—the article mentioned Lucy Calkins’s controversial resource, Units of Study.

The reactions were swift.

My intention wasn’t to promote that resource or ignite debate. I shared it because it reminded me of something I’ve seen again and again in schools:

Great teachers can make any resource work.

The classroom featured in the article showcased fourth graders synthesizing across genres and time periods. They wrote research papers on the American Revolution, compared author perspectives, and held multiple truths at once.

It was deep, intellectually rigorous work—work that should resonate regardless of where you stood in the larger literacy conversation.

But what followed surprised me.

The post sparked a cascade of passionate responses. Some were affirming. Others were skeptical. Many were deeply thoughtful.

And as I reread the thread later—curiously, not defensively—I realized something deeper was surfacing:

The debate wasn’t just about one resource. It was about how we define and scale excellent literacy instruction across very different realities.

Not Just a Debate Over Programs—A Debate Over Realities

We often frame literacy conversations around which programs or resources are “best.” But maybe we’re asking the wrong question.

More helpful questions might be:

What’s the connection between a purchased literacy resource and the curriculum a district creates from it?

Should we be talking about/assessing the quality of a district’s purchased resources or a district’s literacy curriculum?

Who creates a district curriculum, and under what conditions?

Are some purchased resources easier to transform into a curriculum than others?

Can the process of resource to curriculum spark teacher growth and have a positive impact on students?

Should a district’s current context shape how this resource-to-curriculum process unfolds?

📌 Here’s a helpful podcast that explores this distinction between “resource” and “curriculum.”

What the Comments Revealed: Three Realities, Three Camps

As the conversation unfolded, three distinct camps emerged—each shaped by different realities, each holding a version of the truth:

The “Great Teaching Can Make Anything Work” Camp

These educators emphasized that the true lever is the teacher—not the tool. Their knowledge, professional judgment, and in-the-moment decisions matter more than what’s printed on the page.

The “This Program Works for Us” Camp

These voices acknowledged the resource wasn’t perfect—but through coaching, leadership, and smart implementation, it became a platform for student success. They didn’t follow it blindly; they adapted it thoughtfully.

The “Only Evidence-Based Programs” Camp

This group held firm: only resources grounded in both research and evidence should be used. For them, scaling excellence requires minimizing variability—not relying on exceptional teachers to carry the load.

At first, the differences felt stark.

But then it hit me:

We weren’t reacting the same way because we weren’t living in the same realities.

Until we fully acknowledge how systems differ—rural and urban, big or small, under-resourced and well-supported—we’ll keep talking past each other.

The Three Truths About Scaling Literacy

These truths aren’t in conflict. They’re tensions we must hold together if we want real progress.

Truth #1: We Must Define and Scale Excellence Thoughtfully

Calls for scalable excellence are valid—and often begin with purchasing evidence-based resources.

For some districts, that’s the right move.

But for others there can be a different reality.

In one district I worked with, test scores rose significantly in a single year. They didn’t purchase a new resource. Instead, teachers, leaders, and coaches came together voluntarily to revise units from an imperfect resource—grounding their revision in the science of reading, writing, and learning.

The result? A thoughtfully adapted, research-aligned, district-built curriculum.

Should they be forced to change course simply because the original resource wasn’t considered evidence-based—even though their revised curriculum produced positive results?

And here’s another layer: Many programs earn the “evidence-based” label because they had the funding for large-scale studies.

But what about the teachers in small towns creating literacy curriculum that positively affects students?

Or small consulting teams moving student progress in big ways—but without access to randomized controlled trials?

If we only use resources that have been studied, we risk ignoring great work that hasn’t been.

📌Check out this episode of Schoolutions where I chat with Olivia about creating effective curriculum alongside teachers.

Truth #2: Scaling Excellence Requires More Than Materials

Evidence-based resources bring structure—but they’re not the whole story.

John Hattie reminds us:

“It’s not the resources that make the change. It’s the thinking that goes on moment to moment in the classroom.”

In other words: a program doesn’t teach—a teacher does.

What if we studied not just what materials “work,” but which teachers make the biggest difference—and how?

What if those findings shaped coaching, professional development, and teacher prep programs?

In the district I mentioned, improved outcomes weren’t just about the curriculum they created. They were also about:

Shared knowledge around reading, writing, and learning

Collaborative redesign

Coaching and demonstration lessons in classrooms that focused on refining instructional moves

A commitment in those classrooms to studying teaching that accelerated learning and adjusting what stalled it

Their success came not just from fidelity to the curriculum they created, but from a careful study of how students responded to that instruction. That’s a key part of scaling excellence: studying which teacher decisions accelerate learning—and which stall it.

📌 Check out John Hattie’s book to think more about these ideas.

📌Take a look at John Hattie’s podcast about scaling excellence. Here is another more recent Schoolutions Podcast featuring John Hattie talking about teacher excellence.

📌While I don’t agree with everything in this piece, (stay tuned I write about it in detail in next week’s article) it raises important questions about whether program changes alone are enough to achieve excellence—and it’s worth a read.

📌Here is an article I have written that shows educators a way to map district curriculum.

Truth #3: Great Systems—and Great Teachers—Look Different Around the World

Countries like Finland and Singapore scale excellence not through pre-packaged programs, but through deep investments in teacher preparation, shared planning, and professional trust.

Even here in the U.S., we see the same divide:

Some districts want a ready-made resource with minimal customization.

Others want space to analyze, adapt, and co-construct curriculum.

One commenter put it this way:

“I had to change the program so much, I felt like a curriculum writer.”

No one should be forced into that role—but some thrive in it. I’m confident that the process of making those adaptations helps an interested educator become a stronger teacher.

So here’s the real question:

Can we support both models—high-fidelity implementation and deep co-construction—when each is chosen with care, data, and community input?

Maybe that’s where the nuance lives.

📌Watch this Schoolutions episode where a teacher/author talks about the differences between teaching in the US and Denmark.

Bringing It All Together: Scale the Thinking, Not Just the Program

Here’s what I keep coming back to:

Scaling excellence is the goal. But the path may look different depending on the district.

If we try to standardize the how, we may trade excellence for mediocrity.

Scaling literacy isn’t about copying someone else’s playbook. It’s about:

Building teacher capacity

Studying what worked—not to replicate, but to understand why

Supporting systems in applying that thinking to their own realities

So instead of only asking “What works?” let’s also ask:

📌 What’s your reality?

📌 What materials and professional knowledge will help you succeed in your context?

📌 How can we scale teacher expertise alongside strong resources—not just the materials themselves?

★A district might have a great curriculum, but haven’t scaled teacher excellence yet, OR they might have scaled teacher expertise but don’t yet have a great curriculum.

A Final Word: Scaling With Eyes Wide Open

Recently, my sixth-grade daughter said to me:

“Mom, kids just hate school these days.”

And I told her: It doesn’t have to be that way.

I am confident that is true.

John Hattie’s work reminds us that while academic gains matter, student engagement is also essential. It’s not just a “nice-to-have”—it’s a key factor in long-term outcomes that test scores don’t fully capture.

So here’s my invitation:

Let’s lead with curiosity, not certainty.

Let’s scale the teachers who make a difference—not just the tools they’re handed.

Let’s define excellence not by one version of reality.

Just like the image of equity and justice, scaling literacy requires more than equal materials—it calls for thoughtful support tailored to each district’s reality.

What realities are shaping literacy in your setting?

I’d love to hear what you’re seeing—and what questions you're asking.

Because one reality isn’t enough.

And scaling with nuance might just be the most powerful move we can make.

📌Want to read other articles I’ve written about constructive literacy dialogue? Read this, and this.

📌Want to get your school/district or community inspired about scaling with nuance? Book a keynote on this topic with me. It’s a perfect way to launch the school year or a professional conference.

Sharing is welcome! Please feel free to share the link so others can read, but please don’t print, photocopy, or redistribute without permission.

📌Want full access to all of my articles?

→ Become a paid subscriber: Paid subscribers access to the full archive (Over 50 articles and growing by the day). plus 4-8 new articles per month (half are available to everybody for 24 hours. and the other half are only for paid subscribers.

If my thinking resonates with you, I’d love to help you customize it for your school or district.

📌 Need tools for ELA instruction? My Literacy Toolkit has templates and planning guides and curated videos designed for coaches and teachers.

📌 My mentor text bundles include clear mentor texts with a key that explains each sentence.

📌 Want direct support? I offer coaching sessions to help teams develop strong, sustainable coaching models.

📌Want me to work directly with your school or district? Sign up for a discovery call.

📌 Want to learn with me over the summer? Sign up for LMC’s Summer Literacy Series If you sign up for all five sessions, you get a 10% discount. If you are a paid subscriber to my Substack you get an additional 10% off.

📌Want me to work directly with your school or district? Sign up for a discovery call.

📌Make sure to visit my website.

📌Check out my most recent book, "We-Do" Writing for a research aligned framework for how to support writing instruction and curriculum.

📌My book Self-Directed Writers will ensure that all of your students are engaged, self-directed and motivated writers.

📌My book Don't Forget to Share shows you how to leverage conversation to improve writing.

📌Check out my article 6 Qualities for a Strong Writing Curriculum

(This post may contain affiliate links.)

There is so much wisdom here that applies to our current situation. Here's one piece of wisdom you cite from John Hattie:

“It’s not the resources that make the change. It’s the thinking that goes on moment to moment in the classroom.”

That moment to moment thinking is sometimes called "contingent scaffolding"--we make decisions contingent upon how students are responding to the lesson. This is important because if students just don't get it, it doesn't matter where the 'it' came from originally--it needs fixing.

I'm glad you're out there contemplating all the important questions you pose.